Yuri shakes his head. “I don’t want to be remembered at all,” Yuri says. “If being remembered means being dead.”

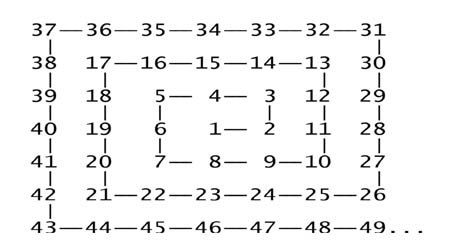

In a Pearls Before Swine comic strip by Stephen Pastis, the “cute” characters talk about how everybody, in the end, is forgotten. You remember a famous name from a hundred, five hundred, or a thousand years ago. But the more you go back in time, the less people you “remember.”

“Eventually,” the cute character says, “We’re all forgotten, even the best ones among us.”

Somebody said sometime ago, and I’m not sure now if he had something to do with Freud, that it was only the human ego that pushes us to delude ourselves of our sense of importance. Whenever we think of our own personal worth, we tend to exaggerate it. We tend to feel “big.” We tend to see ourselves as if we’re the center of the universe. And indeed, for many centuries before the first breed of upstarts like Galileo Galilei and Giordano Bruno, people everywhere, even ordinary peasants, were sure the universe was made for them. That man was the apex of creation; that there was in fact a “creation.” And that everything else revolved around this blob of mud called “Earth.”

[The big, fat human ego]

These days, somebody like Raul Gonzales would merely roll his eyes and say: “That’s bullshit.”I might be walking down that road with my devil-may-care swagger, and I‘d meet Raul Gonzales with his needle, ready to pop my bubble.

I might say, “I am a big-shot cyberjock.”

Raul Gonzales would just say: “That sounds like Dinky Soliman’s dung.”

I might say, “You know what, my dick is bigger than Las Pinas City.”

Raul Gonzales would just say: “That’s the stinkiest dog turd I’ve ever smelled.”

Because while Freud’s Ego and Superego would sing in unison about one’s sense of significance, there’s the Id somewhere, lurking in the dark caverns of our heads, always devoted to remind us we’re just animals.

Animals who can talk. And fuck. And brag about it.

One of my favorite scenes in Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 that hits it home so deeply is when Snowden lies on the plane’s floor, the guy’s intestines and lunch slipping out of his blasted torso, and Yossarian staring at it all and finally getting it—finally understanding that man is garbage.

I once told somebody I’m not here to bring beauty to the universe or change this fucking world. I’m not here to make any difference. That was back in those days when people expected wonderful things to come out of my hat, and were disappointed.

I told that same somebody, If you believe that crap, I’ll tell you another. I said, All those kids want to “make a difference.” Now, this planet is a bleeding mess. Everybody you meet down the road, they want to change the world. Now, look at this. Is this the planet you want? A world created by all sorts of crusaders, all sorts of upstarts out to launch their own revolution.

It’s all pap. There are days you’re just tired of it all. You see somebody say on TV, “My dream is to make a difference.” I scratch my head and wonder, how do you do that? The universe is a swirling mass of change, and it churns every moment. How do you add more shit to the status quo, when the status quo itself is a quick-shifting neon light in any Malate trance club?

Besides, “making a difference” is one of those insufferably crappy lines we love serving ourselves; it’s in the same hackneyed league as “be yourself” or “the greatest good for the greatest number.” Lines nobody really thinks over, lines that we use as ready resource when the need to masturbate strikes or when there’s the sudden craving to slake off some deep personal emptiness.

Human beings are funny. First, they acquire some new evolutionary equipment like the cerebral cortex, and they begin “thinking” that everything they see is made for them. Then, they build on the tale and reinforce it for generations until they begin taking the myth as “truth.” Until nobody remembers that the first guy who told it wove it around a bonfire just to entertain the tribe's kids. Until nobody remembers we’re just articulate animals, after all.

It’s usually fun to listen to the mass of people. But eventually, the fun wears thin. Sometimes, I feel like I'd rather just sit down and stare at my balls till kingdom come.

***

For other Bullshit Meister posts, see:

Wrongness

League of Monsters

Friday Evening Kitsch

The State of the Art

Goodbye, and Thanks for all the Crap

Tags: